I like Progressive Web Apps. I like the model it offers for how you build good, solid, reliable web sites and apps. I like the principle platform API - service worker - that enables the PWA model to work.

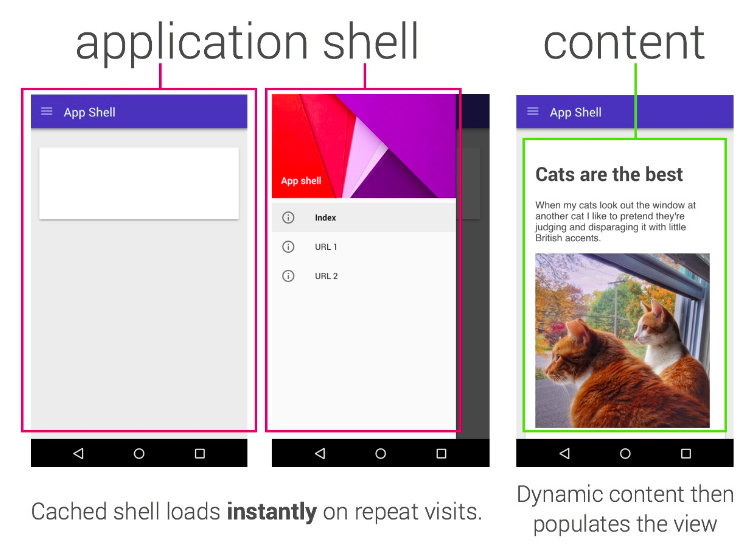

One of the traps that we have fallen into is “App Shell”. The App Shell model says that your site should present a complete shell of your application (so that the experience something even when you are offline) and you then control how and when to pull in content.

The App Shell model is roughly analagous to a “SPA” (Single Page App) — you load the shell, then every subsequent navigation is handled by JS directly in your page. It works well in many cases.

I don’t belive that App Shell is the only nor the best model, and as always your choice varies from situation to situation; my own blog for example uses a simple “Stale-Whilst-Revalidate” pattern every page is cached as you navigate around the site and updates will be displayed in a later refresh; in this post I would like to explore a model that I have recently experimented with.

To App Shell or not App Shell

In the classic model of App Shell it is nearly impossible to support a progressive render and I wanted to achieve a truely “Progressive” model for building a site with service worker that held the following properties:

- It works without JS

- It works when there is no support for a Service Worker

- It is fast

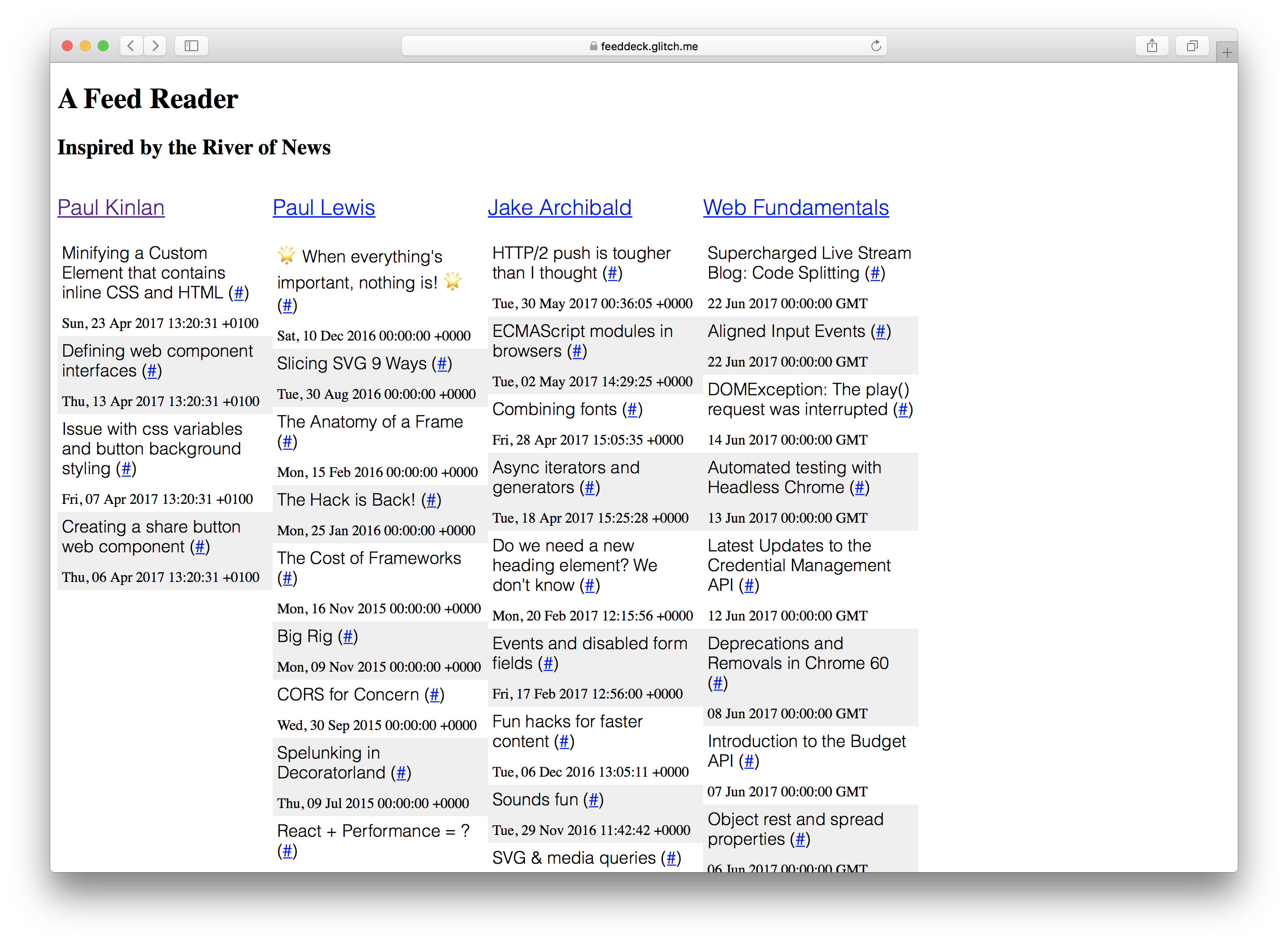

I set out to demonstrate this by creating a project that I’ve always wanted to build: A River of News + TweetDeck Hybrid. For a given collection of RSS feeds render them in a column fashion.

The “Feed Deck” is a good reference experience for experimenting with Service Worker and progressive enhancement. It has a server rendered component, it has the need for a “shell” to show something to the user quickly and it has dynamically generated content that needs to be updated regularly. Finally because it is a personal project I don’t need too much server infrastructure for saving user configuration and authentication.

I achieved most of this and I have learned a lot during the process. Some things still require JS, but the application in theory functions without JS; I long for NodeJS to have more in common with DOM APIs; I built it entirely on Chrome OS with Glitch but this final piece is a story for another day.

I set some definitions of what “Works” means early on in the project.

- “It works without JS” — content loads on the screen and there is a clear path for it for everything working without JS in the future (or there is a clear justification about why it was not enabled). I can’t just say “nah”.

- “It works when there is no support for a Service Worker” — everything should load, function and be blazingly fast but I am happy if it doesn’t work offline everywhere.

But that wasn’t the only story, if we had JS and support for a service worker, I had a mandate to ensure:

- It loaded instantly

- It was reliable and have predictable performance characteristics

- It worked fully offline

Mea culpa: If you look at the code and you run it in an older browser there is a strong chance it won’t work, I did choose to use ES6, however this is not an unsurmountable hurdle.

If we were to focus on build an experience that functioned without JavaScript enabled then it holds that we should render as much as possible on the server.

Finally, I had a secondary goal: I wanted to explore how feasible it was to share logic between your Service Worker and you Server…. I tell a lie, this was the thing that excited me the most and a lot of the benefits of the progressive story fell out of the back of this.

What came first. The Server or the Service Worker?

It was both at the same time. I have to render from the server, but because the service worker sits between the browser and the network I had to think about how the two interplayed.

I was in a lucky position in that I didn’t have a lot of unique server logic so I could tackle the problem holistically and both at the same time. The principles that I followed were to think about what I wanted to achieve with the first render of the page (the experience that every user would get) and subsequent renders of the page (the experience that engaged users would get) both with and without a service worker.

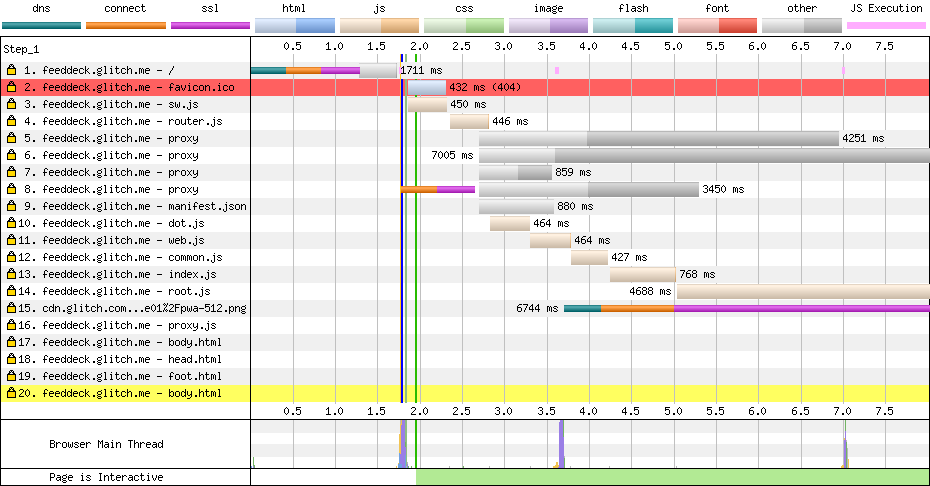

First render — there would be no service worker available so I needed to ensure that the first render contained as much of the page content as possible and have it generated on the server.

If the user has a browser that supports service worker then I can do a couple of

interesting things. I already have the template logic created on the server and

there isn’t anything special about them, then they should be the exact same

templates that I would use directly on the client. The service worker can

fetch the templates at oninstall time and store them for later use.

Second render without service worker — It should act exactly like a first render. We might benefit from normal HTTP Caching, but the theory is the same: render the experience quickly.

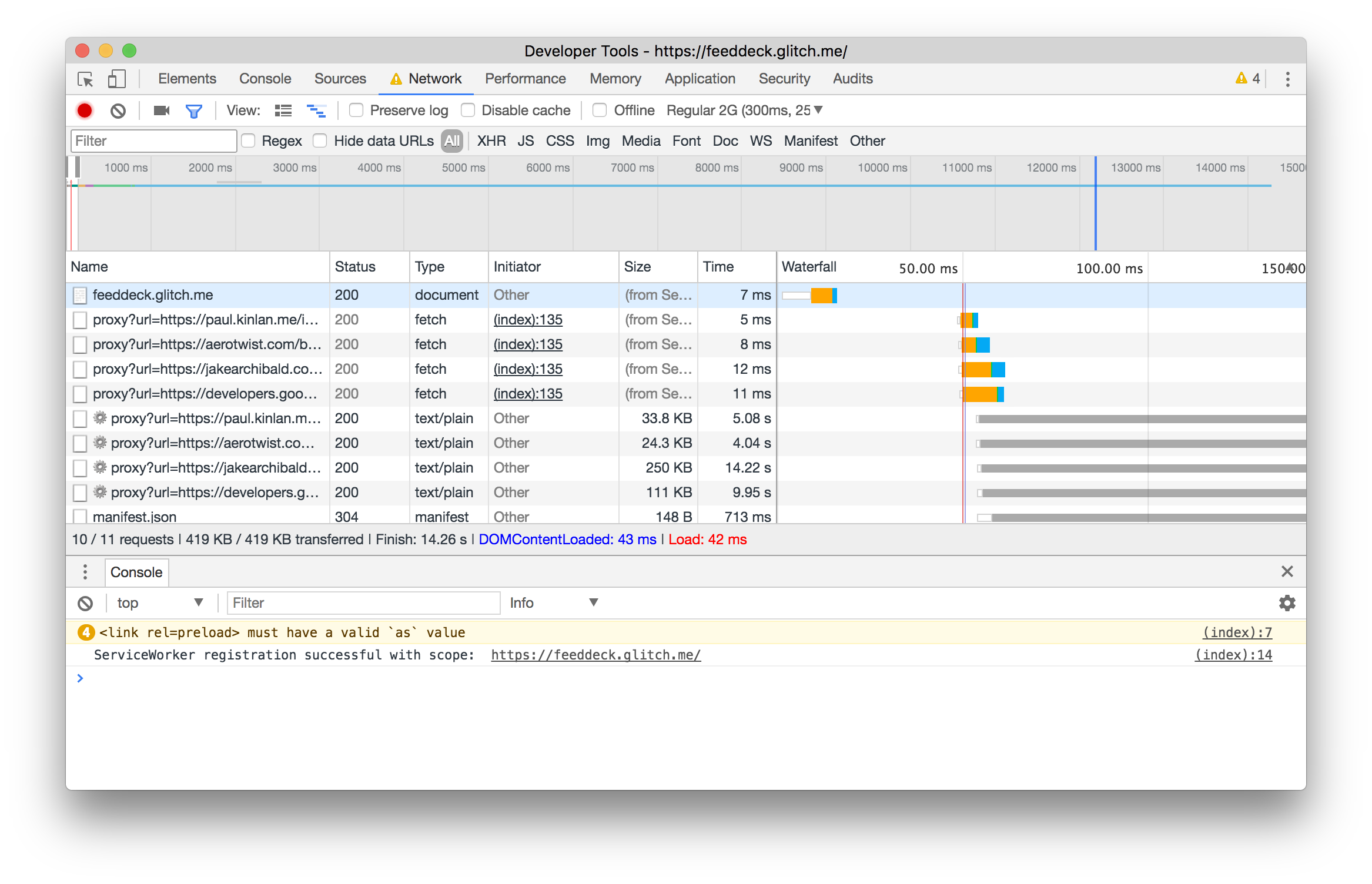

Second render with service worker — It should act exactly like a first server render, but, all inside the service worker. I don’t have the traditional shell. If you look at the network all you see is the fully stitched together HTML: structure and content.

“The render” — Streaming is our friend

I was trying to be as progressive as possible which means that I need to render as much as possible on the server quickly. I had a challenge, if I merged all the data from all the RSS feeds then the first render would be blocked by network requests to RSS feeds and thus we would slow down the first render.

I chose the following path:

- Render the head of the page — it’s relatively static and getting this to the screen quickly aides with percieved performance.

- Render the structure of the page based on the configuration (the columns) — for a given user this is currently static and getting it visible quickly is important for users.

- Render the column data if we have the content cached and available, we can do this on both the server and service worker

- Render the footer of the page that contains the logic to dynamically update the contents of the page periodically.

With these constraints in mind, everything needs to be asynchronus and I need to get everything out on the network as quickly as possible.

There is a real dearth of Streaming templating libraries on the web. I used streaming-dot by my good friend and colleauge Surma which is a port of the templating framework doT but with added generators so that it can write to a Node or DOM Stream and not block on the entire content being available.

Rendering the column data (i.e, what was in a feed) is the most important piece and this at the moment requires JavaScript on the client for the first load. The system is set up to be able to render everything on the server for the first load but I chose not to block on the network.

If the data has already been fetched and it is available in the service worker then we can get this out to the user quickly even if it can quickly become stale.

The code to render the content whilst being aysnc is relatively procedural and follows the model described earlier: We render the header to the stream when the template is ready, then render the body contents to the stream which in turn may be waiting on content which when available will also be flushed to the stream and finally when everything is ready we add in the footer and flush that to the response stream.

Below is the code that I use on the server and the service worker.

const root = (dataPath, assetPath) => {

let columnData = loadData(`${dataPath}columns.json`).then(r => r.json());

let headTemplate = getCompiledTemplate(`${assetPath}templates/head.html`);

let bodyTemplate = getCompiledTemplate(`${assetPath}templates/body.html`);

let itemTemplate = getCompiledTemplate(`${assetPath}templates/item.html`);

let jsonFeedData = fetchCachedFeedData(columnData, itemTemplate);

/*

* Render the head from the cache or network

* Render the body.

* Body has template that brings in config to work out what to render

* If we have data cached let's bring that in.

* Render the footer - contains JS to data bind client request.

*/

const headStream = headTemplate.then(render => render({ columns: columnData }));

const bodyStream = jsonFeedData.then(columns => bodyTemplate.then(render => render({ columns: columns })));

const footStream = loadTemplate(`${assetPath}templates/foot.html`);

let concatStream = new ConcatStream;

headStream.then(stream => stream.pipeTo(concatStream.writable, { preventClose:true }))

.then(() => bodyStream)

.then(stream => stream.pipeTo(concatStream.writable, { preventClose: true }))

.then(() => footStream)

.then(stream => stream.pipeTo(concatStream.writable));

return Promise.resolve(new Response(concatStream.readable, { status: "200" }))

}

With this model in place, it was actually relatively simple to get the above code and process working on the server and in the service worker.

Unified logic server and service worker logic — hoops and hurdles

It was certainly not easy to get to a shared code base between server and client, the Node + NPM ecosystem and the Web JS ecosystem are like genetically identical twins that have grown up with different families and when they finally meet there are many similarities and many differences that need to be overcome… It sounds like a great idea for a movie.

I chose to prefer Web across the project. I decied upon this because I don’t want to bundle and load code in to the user’s browser, but rather I could take that hit on the server (I can scale this, the user can’t), so if the API wasn’t supported in Node then I would have to find a compatible shim.

Here are some of the challenges I faced.

A broken module system

As both the Node and Web Ecosystem grew up they both developed different ways of componentizing, segmenting and importing code at design time. This was a real issue when I was trying to build out this project.

I didn’t want to CommonJS in the browser. I have an irrational desire to stay away from as much build tooling as possible and add in my despise of how bundling works, it left me not a lot of options.

My solution in the browser was to use the flat importScripts method, it works

but it is dependent on very specific file ordering, as can be seen in the

service worker like so:

sw.js

importScripts(`/scripts/router.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/dot.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/platform/web.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/platform/common.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/routes/index.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/routes/root.js`);

importScripts(`/scripts/routes/proxy.js`);

And then for node, I used the normal CommonJS loading mechanism in the same

file, but they are gated behind a simple if statement to import the modules.

if (typeof module !== 'undefined' && module.exports) {

var doT = require('../dot.js');

...

My solution isn’t a scalable solution, it worked but also littered my code with, well code that I didn’t want.

I look forward to the day where Node supports modules that the browsers will

support… We need something simple, sane, shared and scalable.

If you check out the code, you will see this pattern used in nearly every shared file and in many cases it was needed because I needed to import the WHATWG streams reference implementation.

Crossed streams

Streams are probably the most important primitive that we have in computing (and probably the least understood) and both Node and the Web have their own completely different solutions. It was a nightmare to deal with in this project and we really need to standardize on a unified solution (ideally DOM Streams).

Luckily there is a full implementation of the Streams API that you can bring in to Node, and all you have to do is write a couple of utilities to map from Web Stream -> Node Stream and Node Stream -> Web Stream.

const nodeReadStreamToWHATWGReadableStream = (stream) => {

return new ReadableStream({

start(controller) {

stream.on('data', data => {

controller.enqueue(data)

});

stream.on('error', (error) => controller.abort(error))

stream.on('end', () => {

controller.close();

})

}

});

};

class FromWHATWGReadableStream extends Readable {

constructor(options, whatwgStream) {

super(options);

const streamReader = whatwgStream.getReader();

pump(this);

function pump(outStream) {

return streamReader.read().then(({ value, done }) => {

if (done) {

outStream.push(null);

return;

}

outStream.push(value.toString());

return pump(outStream);

});

}

}

}

These two helper functions were only used in the Node side of this project and

they were used to let me get data into Node API’s that couldn’t accept

WHATWG Streams and likewise to pass data into WHATWG Stream compatible APIs

that didn’t understand Node Streams. I specifically needed this for the fetch

API in Node.

Once I had Streams sorted, the final problem and inconsistency was Routing (coincidentally this is where I needed the Stream Utils the most).

Shared routing

The Node ecosystem, particularly Express is incredibly well known and amazingly robust, but we don’t have a shared model between client and service worker.

Years ago I wrote LeviRoutes, a

simple browser side library that handled ExpressJS like routes and hooked into

the History API and also onhashchange API. No one used it but I was happy. I

managed to dust of the cobwebs (make a tweak or two) and deploy it in this

application. Looking at the code below you ca see that my routing is nearly

the same.

server.js

app.get('/', (req, res, next) => {

routes['root'](dataPath, assetPath)

.then(response => node.responseToExpressStream(res, response));

});

app.get('/proxy', (req, res, next) => {

routes['proxy'](dataPath, assetPath, req)

.then(response => response.body.pipe(res, {end: true}));

})

sw.js

// The proxy server '/proxy'

router.get(`${self.location.origin}/proxy`, (e) => {

e.respondWith(routes['proxy'](dataPath, assetPath, e.request));

}, {urlMatchProperty: 'href'});

// The root '/'

router.get(`${self.location.origin}/$`, (e) => {

e.respondWith(routes['root'](dataPath, assetPath));

}, {urlMatchProperty: 'href'});

I would love to see a unified solution that brings the service worker

onfetch API into Node.

I would also love to see an “Express” like framework that unified Node and Browser code request routing. There were just enough differences that meant I couldn’t have the same source everywhere. We can handle routes nearly exactly the same on the client and the server, so we are not that far away.

No DOM outside of the render

When the user has no service worker available, the logic for the site is quite traditional, we render the site on the server and then incrementally refresh the content in the page through a traditional AJAX polling.

The logic uses the DOMParser API to turn an RSS feed into something that

I can filter and query in the page.

// Get the RSS feed data.

fetch(`/proxy?url=${feedUrl}`)

.then(feedResponse => feedResponse.text())

// Convert it in to DOM

.then(feedText => {

const parser = new DOMParser();

return parser.parseFromString(feedText,'application/xml');

})

// Find all the news items

.then(doc => doc.querySelectorAll('item'))

// Convert to an array

.then(items => Array.prototype.map.call(items, item => convertRSSItemToJSON(item)))

// Don't add in items that already exist in the page

.then(items => items.filter(item => !!!(document.getElementById(item.guid))))

// DOM Template.

.then(items => items.map(item => applyTemplate(itemTemplate.cloneNode(true), item)))

// Add it into the page

.then(items => items.forEach(item => column.appendChild(item)))

Accessing the DOM of the RSS feed using the standard APIs in the browser was incredibly useful and it allowed me to use my own templating mechanism (that I am rather proud of) to update the page dynamically.

<template id='itemTemplate'>

<div class="item" data-bind_id='guid'>

<h3><span data-bind_inner-text='title'></span> (<a data-bind_href='link'>#</a>)</h3>

<div data-bind_inner-text='pubDate'></div>

</div>

</template>

<script>

const applyTemplate = (templateElement, data) => {

const element = templateElement.content.cloneNode(true);

const treeWalker = document.createTreeWalker(element, NodeFilter.SHOW_ELEMENT, () => NodeFilter.FILTER_ACCEPT);

while(treeWalker.nextNode()) {

const node = treeWalker.currentNode;

for(let bindAttr in node.dataset) {

let isBindableAttr = (bindAttr.indexOf('bind_') == 0) ? true : false;

if(isBindableAttr) {

let dataKey = node.dataset[bindAttr];

let bindKey = bindAttr.substr(5);

node[bindKey] = data[dataKey];

}

}

}

return element;

};

</script>I was very pleased with myself until I realised that I couldn’t use any of this on the server or in a service worker. The only solution that I had was to bring in a custom XML parser and walk that to generate the HTML. It added some complication and left me cursing the web.

In the long run I would love to see some more of the DOM API’s brought in to workers and also supported in Node, but the solution I have works even if it isn’t optimal.

Is it possible?

There are really two questions in this post:

- Is it practical to build systems share a common server and service worker?

- Is it possible to build a fully progressive Progressive Web App?

Is it practical to build systems share a common server and service worker?

It is possible to build systems share a common server and service worker but is it practical? I like the idea, but I think it needs more research because if you are going JS all the way, then there are a lot of issues between the Node and Web platform that need to be ironed out.

Personally I would love to see more “Web” APIs in the Node ecosystem.

Is it possible to build a fully progressive Progressive Web App?

Yes.

I am very pleased that I did this. Even if you don’t share the same language on client as on service, there are a number of critical things that I think I have been able to show.

- AppShell is not the only model that you can follow, the important point is that service worker you get the control over the network and you can decide what is best for your use case.

- It is possible to build a progressively rendered experience that uses service worker to bring performance and resilience (as well as an installed feel if you like). You need to think holistically, you need to start with rendering as much as you can on the server first and then taking control in the client.

- It is possible to think about experiences that are built “trisomorphically” (I still think the term isomorphic is best) with a common code base, a common routing structure and common logic shared across client, service worker and server.

I leave this as a final thought: We need to investigate more about how we want to build progressive web apps and we need to keep pushing on the patterns that let us get there. AppShell was a great start, it’s not the end. Progressive rendering and enhancement are the key to the long term success of the web, no other medium can do this as well as the web.

If you are interested in the code, check it out on Github but you can also play with it directly and remix it on glitch